When you see a guitar god deliver a perfect solo on stage, it often looks completely effortless. Like it’s the most natural thing in the world. Every note is where it needs to be. The whole solo sounds convincing from start to finish.

So why is it then, that so often when we try ourselves thing sound a little… underwhelming? You might feel your playing sounds stale, boring or unnatural at times.

In this article, we’ll dig into some of the biggest problems guitarists face when soloing: the ‘enemies’ of great guitar solos. We’ll analyse the problem and I’ll give you a number of solutions to overcome these obstacles. (Spoiler: we'll explore how to tap into your musicality to make your solos sound better.) This is a choose your own adventure-style article, so select the villains of your story and let’s find out what weapons you have at your disposal to beat them!

The Five Enemies of Great Guitar Solos

Villain #1 - Scale Patterns My solos sound like running up and down a scale

Villain #2 – More Scale Patterns I'm Stuck in a box or scale pattern

Villain #3– The Fretboard My solos sound ‘guitarish’ and I want to sound more melodic

Villain #4 – Your Inner Critic This sucks, my playing should be more interesting…

Villain #5 - Your Theoretical Mind I’m lost in scales, modes, arpeggios and so on…

Villain #1 – Scale Patterns

“My solos sound like running up and down a scale”It might sound a little weird: how can learning scale patterns make your soloing sound worse? To answer this question, let’s consider how most guitarists are taught to play a solo. The number 1 advice is: learn the minor pentatonic scale. It’s pretty easy to learn, memorise and play. And I admit, it will get you up and running fairly quickly and make you sound sort of decent.

The issue with this is that a scale is often presented as a ‘correct note map’ to the fretboard. The message is: ‘You can play any of these notes and it won’t sound wrong’. And while it’s true that it won’t sound wrong, it usually also won’t sound right.

Think of it like this. Say you’re visiting Paris and you’ve prepared by learning a bunch of French phrases. You arrive and get in a cab and the driver asks how you’re doing today. You answer “Hello, my name is Judith.” You get to your hotel and you’re asked how your flight was. You reply: “Thank you, how are you?”. People will understand what you’re saying because it’s in the correct language, but they’ll still look at you funny because it doesn’t make any sense in the context of your conversation. It’s not wrong per se, but it certainly also isn’t right.

When you sound like a scale, you’re doing pretty much the same thing. You’re simply repeating a bunch of notes you learned, instead of listening to the musical context and responding to what you hear. This is a typical guitar and piano problem. Singers, for example, have few problems with sounding 'scale-like' when they improvise. The reason is that you need to first imagine a note in your mind before you can sing it. You need to think of a pitch before you can manipulate your vocal cords to produce that pitch. (Fun exercise: try to imagine a note in your mind, but then sing a different note. It’s… weird, if not impossible.)

But with a guitar or piano, you can just press a ‘button’ and voila, you get a note! It’s possible to play a note without imagining it first. And so, it’s possible to play without listening to your musical imagination. If you sound like a robot hitting theoretically correct notes, that’s exactly your problem: your musical imagination is not running the show.

So what’s the solution? How do you start sounding more natural and musical instead of running up and down scales? Here are two things you should try.

Solution #1: Tune into Your Musical Imagination

Instead of a scale or fretboard pattern telling us what to play, we need to start with what we want to play. In other words: we need to play from our musical imagination.

This might sound a little daunting, but don’t worry. There are simple ways to get started with tuning into your musical imagination and playing what you hear. I’ve written about how to do this in other articles in much more detail, so I recommend you check them out.

For various exercises that will help you tune into your musical imagination and improvise, check out How To Improvise On Guitar. Section 2 will give you a few vocal exercises and section 3 will offer some ways to practice on guitar.

To get a clearer picture of how playing guitar by ear works and how to learn it, check out How To Play Guitar By Ear.

Solution #2: Expand your vocabulary

When you play from your musical imagination when you’re improvising, you’ll already sound much better than when you’re putting a scale pattern in the driver’s seat. But sometimes, you’ll try, but it’ll seem like your musical imagination simply doesn’t have much to say. This is usually the case if you’re trying to improvise in a genre or style of music you’re not overly familiar with.

The problem here is that you don't have enough vocabulary yet. Just like when you’re learning a new language, you need to learn words and the typical phrases that are used in the language. When you’re visiting Paris, knowing more French phrases would allow you to respond to situations in a natural way. In the same way, learning more riffs, licks and phrases that are often used in a musical genre, will help you play more musical and natural solos.

A great way to expand your vocabulary is to learn solos by all the great players that came before you. As you learn more solos, you’ll start to recognize the same licks and phrases coming up. Inevitably, you’ll start to pick up the phrases you like and they’ll become part of your musical vocabulary.

Sidenote: Isn’t that stealing?I know that this idea of learning other guitarist’s solos makes some players a little uneasy. What about being original? Isn’t it bad to ‘steal’ things from other players? Shouldn’t we come up with our own stuff?

It sounds reasonable at first, but this idea doesn’t hold up when we take a closer look. All great musicians studied the musicians that came before them. You can hear Albert King licks in Jimi Hendrix’ solos. You can hear how Stevie Ray Vaughan was influenced by Hendrix. And in John Mayer solos you can point out phrases he took from B.B. King, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Hendrix. Charlie Parker used to read Stravinski scores on the bus (imagining the music in his mind), looking for interesting melodies to use himself. A good artist borrows, a great artist steals.

Originality isn’t to come up with 100% new things. It’s to create your own unique blend of musical influences.

Villain #2 – More Scale Patterns

I'm Stuck in A Box or Scale Pattern

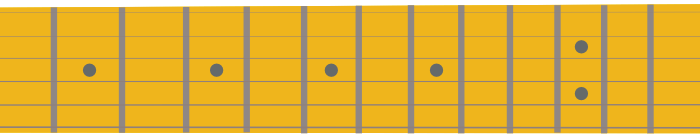

You might've seen many great players playing solos all over the neck, while you tend to stick to the same position over and over again. You might feel stuck in that single ’box’ or pattern on the neck. Seeing guitarists fly around the neck, it can be tempting to double down and think ‘I just need more information’. It might seem you need to learn more shapes, scales, boxes, patterns and arpeggios so that you have more to choose from. It seems reasonable that that will ‘free you up’ by giving you more options.

Now, it’s certainly useful to learn to play in different positions. But if you don’t sound good in just one position, you won’t sound good in two, three or four positions. Sadly, every once in a while, I’ll see someone posting online saying “I was told I needed to learn all the scale positions in order to be able to solo. I’ve spent hours memorising them all, but I still suck.”

So what’s going on here? Let me ask you this: is ‘being stuck in a box’ really your problem? Playing in one position isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If you know how to play a scale in one position, that’s two octaves right there that you can use to make a bazillion different melodies! There are countless world-class solos that are played in just one position. To name a few:

- Oye Como Va by Santana

- The intro to Fleetwood Mac’s Need Your Love So Bad

- Hey Joe, Foxy Lady and Purple Haze by Jimi Hendrix

- The intro to John Mayer’s Gravity

So perhaps, your problem isn’t so much that you’re stuck in the same position. Chances are, your real problem is simply that you don’t like your playing. This could be because you’re playing the same fretboard patterns over and over again (see villain #3 below) or because your inner critic is telling you that what your playing isn’t good enough (see villain #4 below).

But let’s say that indeed your problem is that you’re stuck in that one position. The cause is not a lack of knowledge of scale positions. The reason that you’re ‘stuck’ in that position is that your musical imagination has never forced you out of it. This might be because you never imagined a melody that didn’t fit into the box. But more likely, you weren’t listening to your musical imagination (enough). Instead, you were starting from the fretboard, starting from patterns.

So, how do you tackle this issue? As with the first villain, the most important weapon is the power of your musical imagination. By tuning into what your musical mind comes up with and playing that, you’ll automatically start playing things in different positions. At first this might be just one or two notes that don’t fit into the scale position you’re playing. Slowly, you’ll find yourself moving across the neck. To find out more about how you can learn to play guitar by ear, check out this detailed guide.

There are two other exercises I’d love for you to try as well.1. A great exercise is to play solos on only one string. This works because you can no longer rely on your knowledge of scale positions/shapes on the fretboard. You can’t play anything that’s too fast and you can’t play any licks you have in your system. Just play one note and try to listen to what your musical imagination suggests the next note should be.

2. Another great exercise is to put on some music, any music that you haven’t played before. A playlist on random is perfect. Next, simply start playing along. Play a note and see what it sounds like. If you don’t like it, play a different one. (If a note sounds really rough, just move up or down one fret and it will be better.) Simple as that. The goal of this exercise is to improvise without using your theoretical knowledge. And because you don’t know the song you’re playing along too, you can’t fall back on your knowledge of theory. You just have to rely on your ears. Once you’ve do realise the key of the song, or fall into your comfortable scale shape, skip to the next song. The point of this exercise is to play without having the ‘guard rails’ of a scale shape.

Villain #3– The Fretboard

My solos sound ‘guitarish’ and I want to sound more melodic

What’s great about the fretboard is that that we can learn one chord or scale shape and move it around the neck to play it any key we want to. That’s really pretty awesome. For a piano player, playing a song in the key of C minor instead of B minor, means a totally different ‘landscape’. Visually, on the keyboard C minor and B minor are nothing alike, whereas on the fretboard we simply move up the exact same shape and we’re done. This is great but also not so great. Because that exact scale shape will invite us to play the same things over and over again.

The more you play, the more certain licks, phrases or motives will feel comfortable to play. The hammer-ons, the pull-offs, the way you switch from one scale position to the next…

As guitar players we often start out by learning the minor pentatonic scale. It’s a super easy scale to learn and play, making that our soloing often has a backbone of ‘minor pentatonic’. And while there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, after a while it can start to sound a little stale or at least one-sided. There are so much more sounds we can use to tell interesting musical stories. We can go beyond the comfortable guitar lines we know and love.

Solution #1: Your Musical ImaginationYour musical imagination isn’t limited by what’s comfortable to play on guitar. It pulls musical ideas from all instruments and genres you listen to. The question is: how do you tune into your musical imagination?

One great way is put away your guitar for a moment. Then start a voice memo recording on your phone and put on a piece of music. Take the time to tune into the music and wait until a note or a quick melody pops into your mind. Sing or hum it. Congratulations: you’ve successfully improvised from your musical imagination! The next thing is to figure out how to play what you came up with on guitar. Repeat this process as often as you like. You can even sing entire solos and then figure out your own solo by ear!

This is one of the exercises from my article on playing guitar by ear. The article has a couple of follow-up exercises you might enjoy too, check them out here.

Solution #2: Enhance your melodic mindHere’s a challenge. Grab your guitar and play a famous melody. Beethoven, Miles Davis, Pharell Williams…. It doesn’t matter, as long as it’s a melody. Not a riff, not a lick - a melody. Something you’d sing in the shower. Got that? Excellent, now play ten more.

Surprisingly difficult isn’t it? As guitar players, we play a lot of chords and ‘cool’ guitar lines. But melodies… For some reason, we often leave it to the pianist, saxophone player or singer and wait until the solo comes so we can showcase our mind blowing licks.

It’s weird. Many guitarists can’t play a simple, but beautiful melody to save their life. This is largely because we’re so used to playing stuff that’s comfortable to playing on guitar. But a couple of years ago, I felt a lot of my playing sounded a bit ‘guitarish’. I wanted it to be more melodic.

My teacher told me to learn more melodies and I went a bit overboard and decided to create a list of 100 melodies. I’d use anything I liked. Indie guitar riffs, vocal melodies, movie themes, jazz themes, melodic bass lines from Hip Hop songs… There is and endless amount of strong melodies to choose from.

I found that learning all these amazing melodies, helped me get away from the ‘guitarish’ pentatonic blues lick playing. Creating a list like this will make you explore other less obvious options on the fretboard. It will also make it easier to play all the stuff you hear in your head. The stuff that doesn’t really care whether or not something is ‘comfortable’ or obvious to play on a guitar.

Now, simply learning how to play these melodies will be helpful. But to really get them into your system and ‘own’ them, it’s really important that you figure them out by ear. This will ingrain the music on a much deeper level in your brain. To learn more about figuring out songs by ear, check out this step-by-step guide!

If you’re a StringKick All Access Member, you can get start training your melodic mind right away. I’ve collected 13 of the strongest melodies I could find and created the course Masterful Melodies. The cool thing is that none of these 13 melodies are played on guitar and they're from a range of genres. Nineties pop music, jazz, classical, soundtracks... It's all over the place. With this interactive TAB system, you’ll learn to play each of the 13 melodies by ear.

Check out Masterful Melodies here!

Villain #4 – Your Inner Critic

My playing should be more interesting

You know the feeling. You’re on stage, your moment to shine comes up. You really want to do well. Maybe there’s someone in the audience you really want to impress.

You’re a few notes into the solo and start to wonder:

Was that any good? Hmmm, maybe it’s a little straightforward isn’t it? Kind of an obvious thing to play. What about that new scale I practiced last week? Or wait, I did practice that one really cool lick, maybe I can throw that in and impress the heck out of the audience.

When you start to think like this, things do not end well. The more you try to play well, the worse you do. And the place we want to play at our best? On stage, in front of an audience.

If only we could not care about playing well… Yeah, not very likely to happen. Fortunately, there are ways we can deal with our inner critic and our desire to play well. There are ways to keep thoughts from distracting us and you can better at them with a few exercises you can do at home. Read more about this in my guide How deal with your inner critic on stage.

Villain #5: Your Theoretical Mind

I’m lost in scales, modes, arpeggio’s and so on…

The final villain is sort of a mix of all the villains above. The final boss, if you will.

As you might know, learning scales, arpeggios and music theory can be incredibly beneficial. It can help you understand what you’re playing, hear patterns and connections you’ve never heard before and explore new musical landscapes. Theory can help you understand what your musical imagination comes up with. It can make it easier to play what you hear in your head.

But there are challenges. Sometimes theoretical knowledge can make people sound worse, because it makes them stop listening to their musical imagination. The danger is that theoretical knowledge starts to dictate what you play, making your playing sound bland, boring, ‘scaley’, theoretical or unmusical. It’s something that many guitarists run into at some point.

I suspect this happens because the guitar is such a visual instrument, unlike a trumpet for example. There are shapes and patterns you can learn that ensure you’ll never play a ‘wrong’ note. (Which is a bit short-sighted to say of course, see villain #1.) While this can make it easier to get started with playing solos and improvising, the danger is that you start ‘pressing buttons’ instead of playing music. Yes, all the notes you play will sound like they are in the right scale. In fact, that’s exactly what it will sound like: a bunch of notes in a scale instead of a melodic, musical story.

The solution is to tune into your musical imagination and play whatever you hear in your mind, as I’ve outlined above. But you might be thinking: "Wait a second, so I just shouldn’t bother with music theory at all?!” It raises the question: what role does music theory play in this story?

The short answer is this: “You need to learn everything, then forget everything you learned".

For the slightly longer answer, take a look at this:

- What is 2 + 2?

- Complete the phrase ‘bread and …’

As you read these questions, an answer immediately popped in your head. It is your mind in ‘automatic mode’. You didn’t try to answer the questions, it just happened. It’s fast thinking. Similarly, your mind is in ‘automatic mode’ when:

- you’re driving on an empty road

- you notice that one object is closer to you than another

- you hear a sudden sound and detect where it’s coming from

- you read words on a large bill board

Now take a look at this:

- 17 x 24 = ?

You immediately know this is a math problem and that you can solve it. You also instantly know that 153 and 12,909 are both implausible answers. But without spending some time on the problem, you can’t be sure that the answer isn’t 568. An exact answer didn’t come to mind as you read the question and you can choose whether or not you want to engage with the question to figure it out. Take a moment and try to solve the problem if you haven’t already.

What you’ve just experienced is slow thinking. You’ll notice this is a pretty slow, deliberate and effortful process. You felt the burden of holding all the information in your head, while going through a series of steps to get to the answer (which is 408 by the way).

This is a quick summary of the first couple of pages of Daniel Kahneman’s brilliant book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’. Kahneman demonstrates that we have two mental systems. A fast, automatic and effortless system and a slow system that you can choose to use for complex computations.

So how does this relate to music theory and playing music?

Say you’re playing a solo and think to yourself: “Let me try that new scale I learned last week.” You might get lucky and sound half-decent, but most likely whatever you play will sound forced and unnatural. (I’m speaking from personal experience here – this is something that happened to me all the time when I was at music school and had to learn a ton of new scales etc.)

Contrast that with a situation where that scale has become part of your ‘fast’ system. You hear a melody in your head and instantly know which scale pattern it corresponds with and how to play it. The line sounds good, because it’s pretty difficult to think up stuff that makes no musical sense. (In the same way, when someone says: ‘How are you doing?’, it’s easier to come up with the reply ‘Not too bad, thanks’ than ‘The aliens are coming to paint all our mailboxes purple’. It simply takes a lot less mental effort.)

In other words, we should get music theory to a point where it’s ‘automatic’. It shouldn’t be something that you choose to use, it should just be there. A painter isn’t racking her brain to remember what color you get when you mix blue and red. She simply knows. She isn’t thinking about drawing a ‘circle’, she just does it.

When theory becomes automatic, everything slowly fuses together. You know what a note will sound like, you know what that sound is called, and you know what your fingers have to do… There isn’t one thing that comes first. It all happens simultaneously.

The million dollar question is of course: how do you make theory automatic? How can you make it part of your fast system?

The good news is this. You’ve already put in a ton of work that will help you do this. Listening to music and becoming familiar with all the sounds you’re hearing is the first step. The next is to start learning all the names for these sounds. Music theory helps us describe all of the sounds we hear. What is this chord called? What is the distance between this note and that note? Why does this chord sounds so weird in this song and what do we call that?

It’s key to study real music and figure out how it’s constructed. You need to learn about the building blocks of music and figure out how that relates to the music you love. The more you do this, the more obvious things will become. You might hear a song and immedeately go ‘Oh, this song is in minor’. Or you might hear a chord and automatically think ‘Ooh, that major seventh chord sounds good’. The more you practice, the more automatic and obvious things will become.

Conclusion

That’s it! Hope this guide has given you a deeper understanding of why you sometimes don’t sound as good as you’d like and what you can do about it. With the right kind of practice, you’ll see that your soloing will start to sound more natural and become more enjoyable.

If you have any thoughts or questions, feel free to email me: just (at) stringkick.com.

Become an All Access Member

Get access to All Courses and...

Train Your Ears

Ear training should help you in everyday playing. So instead of doing dry exercises, you’ll be figuring out real music by ear. So you’ll develop your ears, while learning tons of cool songs.

Learn Music Theory

Take super practical theory lessons, made specifically for guitar players. They’ll help you to navigate the fretboard, communicate with band mates and understand how the music you love is constructed.

Develop your Musicality

All courses on StringKick focus on tapping into and developing the musician inside you. By strengthening these skills, your playing will start to feel easier and more natural.

![Title image for How to Improvise On Guitar [Easy Guide]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Improvise-Purple-315x175.png)

![Title image for How to Learn Songs by Ear [Complete Step-by-Step Guide]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Learn-Songs-By-Ear-Orange.png)