Chord names may look like a scary jumble of letters and numbers at first. But once you learn how to read them, they'll become an incredibly useful tool.

Here's how:

- Chord names and symbols allow you to quickly play through a song

- They allow you to easily jot down the chords to a song

- Chord names are a common language for musicians, making it much easier to communicate with band mates, jam buddies or other musician friends.

In short, these are all essential musicianship skills, all things that I focus on with this site!

And so, this article will teach you everything you need to know!

How to use this guide?

So What’s the best way to learn chord names and symbols?

The last thing I want to do is overwhelm you with music theory you don’t understand. So, I’ve divided this guide into different sections, to tailor whatever stage you are in your journey of learning music.

The First Stage: Learn a whole bunch of chords

The ‘experience before theory’ principle is a cornerstone of my music learning philosophy. In short, it means that theory makes a lot more sense when you can connect it to actual music you’ve heard or played.

If you’ve never played a chord like ‘Am7’ or Cmaj7’ before, it will just be so dry and boring to learn the theory behind them!

That means the best way to start understanding chord names, is to simply learn a whole bunch of chords. It sounds simple and it is simple.

So section 1 explains how you can learn the most common and most useful chords on guitar.

The Second Stage: Learn how to read chord names

Section 2 will help you use all these chord names. I’ll explain the basics of how chord names are constructed. Plus: how should you say those chord names out loud?

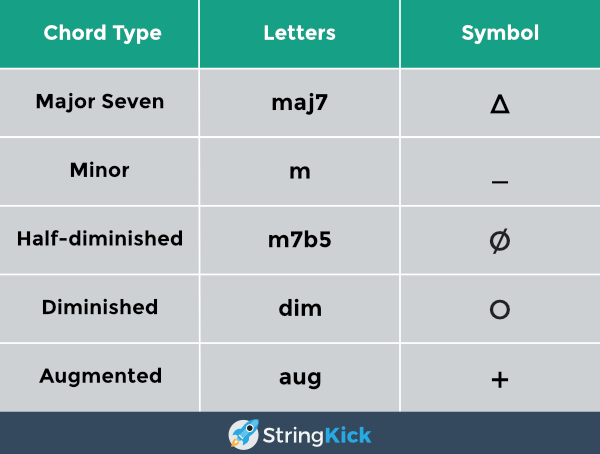

In section 3, you'll learn about other ways of writing these chords, using chord symbols. This section provides an overview of the different ways the exact same chord can be written down using chord symbols like circles, triangles and circles with lines through them.

By the end of these two sections, you’ll know how to say chord names out loud with confidence!The Third Stage: Understand chord names

Section 4 discusses the logic behind chord names. What are those letters and numbers actually referring to? Now, this section does require some knowledge of music theory. In particular, you need to know about sharps and flats, and you should understand what an interval is. (Sidenote: you can learn all about this in Music Theory from Scratch.)SECTION 1

Learn the most important guitar chords

You can divide guitar chords into roughly three ‘levels’:

- Open Chords

- Barre Chords

- Other moveable chord shapes

Let’s take a quick look at each of these.

1. Open Chords

The first guitar chords you’ll ever learn are open chords. They’re relatively easy to play, and still incredibly useful.

Open chords are the ones that you play in the first three frets of the guitar. They’re called ‘open’ because these chords have ‘open’ strings in them. Those are strings that you do pick (with your right hand), but don’t fret (with your left hand).

You might’ve already learned open chords such as Am, C, D, Em and G. But you can also play more advanced open chords such as C7, Gmaj7 and Dm7.

Having a good grasp on these chords, is the foundation for any guitarist. So if you want to learn them, check out Guitar Chord Bootcamp: Open Chords. It will teach you the 24 most open chords, along with a couple dozens songs to practice them with!

2. Barre Chords

Barre chords allow you to play many, many chords that you can't play as open chords. It makes it super easy to play even exotic sounding chords like “C#m7” or “Dbmaj7”. That makes learning to play barre chords a really great way to become more familiar with many different chord names.

Now, this might sound a little complicated, but it doesn’t have to be. Once you understand the power of moving shapes up and down the fretboard, you’ll see that this is actually pretty simple!

Basically, you need two things:

- Know the notes on the low E string, and the A string.

- Know the most important barre chord shapes.

This is exactly what you’ll learn in Guitar Chord Bootcamp: Barre and Beyond. By splitting up everything into bit-size chunks and practicing with dozens of songs, you’ll store all the information ‘in your fingertips’, so to speak.

You can try out the first lessons for free.

3. Other moveable chord shapes

For open chords and barre chords (the first two categories above), I generally recommend you simply remember the shapes. But once you get to this step, it makes a lot of sense to start learning about the theory of chord construction and how that relates to the fretboard. Once you understand that, you can start to change the shapes you know to create exciting, new chords.

This topic is too big to cover in this article (though we’ll get into the basics in section 4), but I’ll give you the things you should learn.

- First, learn intervals. Intervals are nothing more than the distance between two notes. That distance can be large or small. Intervals are crucial: they are the foundation for music theory. They help us understand everything from melodies and scales to chords and chord progressions.

- Next, you want to look into chord construction. You’ll learn how any chord is made up out of a root note (the lowest note in the chord), with certain intervals added to it. Understanding this, will allow you to see the logic behind chord shapes. Checking out the CAGED system is also helpful here.

All of this is covered in Music Theory From Scratch. It’ll show you how intervals work on guitar, and how chord are constructed. You’ll also see all of this logic in action as you analyze dozens of songs in interactive quiz lessons. I might be a little bit biased, but I think it’s pretty awesome.

Naturally, the course is included in your membership if you’re a StringKick All Access Member!

SECTION 2

How to Read Chord Names

This section will to teach you how to say the chord names out loud. So if you come across something like Abmaj7#11, you’ll know to say ‘A flat major seven sharp eleven’. That means that I'm keeping music theory to an absolute minimum here. (If you're interested in the logic behind chord names, scroll down to section 4.)

Root note

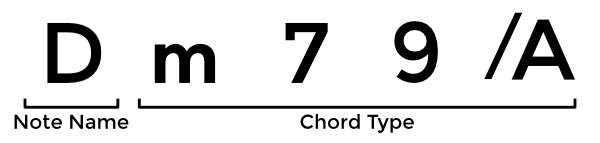

A chord name can be divided into two sections: a note name (i.e. a letter) and everything else.

This note name indicates the lowest note of the chord, which we call the root. This root note is always our starting point. This can be any letter from A to G, which is sometimes be followed by one of two symbols: a sharp (#) or a flat (b):

So these chords are called ‘F sharp’ and ‘B flat’. You get the idea. Here give it a try:

Major and minor

Of course a chord is more than one note. So once we have our root note, we start stacking other notes on top of this root note to build a chord with a certain mood. By choosing our 'ingredients' carefully, we can make chords that sound sweet or gloomy, tense or relaxed, happy or sad. This collection of ingredients is known as the ‘chord type’. Think of it as a recipe that tells musicians which notes they can add to a chord. The chord type is what I called 'everything else' above. Let's update that:

These chord types fall into two big buckets: major and minor. You could roughly say that major chords sound happy and minor chords sound sad and gloomy.

To tell whether a chord is major or minor, simply check if the root note is immediately followed by an ‘m’, which stands for ‘minor’. If there’s an m, you’re dealing with a minor chord. If there’s not an m, you’ll be dealing with a major chord in most cases. (There are a few exceptions that we'll discuss later in this section.) Here, try it for yourself.

When you want to say the name out loud of a major chord, it’s not necessary to say ‘major’. You can simply say the root note. So ‘Db’ is simply ‘D flat’. C# is ‘C sharp’. However ‘Bm’ is ‘B minor’ and ‘Abm’ is ‘A flat minor’. Give it a shot:

Numbers

Hope that went well! The next thing you’ll come across, is a bunch of numbers like ‘6’, ‘7’, ‘b9’ or ‘#11’. For example:

Pronouncing these numbers is simple: just read them out loud. So the above chords are ‘D minor seven’, ‘B seven’ and ‘E seven sharp nine’. Try it:

There is just one exception to this rule: 5. A five indicates that we’re not dealing with a major or a minor chord, but with a power chord. So ‘G5’ is a G power chord. D5 is a D power chord.

Number and letter combinations

There are three set combinations of numbers and letters you might come across:

1. Sometimes a 7 will be preceded by the letters ‘maj’. This indicates that we’re dealing with a major seventh. So Cmaj7 is a ‘C major seven’ chord and Fmaj7#11 is an ‘F major seven sharp eleven’ chord.

2. A 9 might be preceded with ‘add’. So you might come across a ‘Cadd9’ chord or a ‘Ebmadd9’ chord. These are pronounced ‘C add nine’ and ‘E flat minor add nine’.

3. When a chord says ‘sus2’ or ‘sus4’ that means it’s not major or minor: it’s a suspended chord. Typically, we just use the shorthand names ‘sus2’ or ‘sus4’ instead of calling them ‘suspended fourth chord’. So Dsus4 is pronounced ‘Dee sus four’.

Give it a shot:

Three more chord types

We’re almost there, so hang on! There are three more chord types that you’ll come across, though they aren’t as common as most of the chords we’ve discussed so far.

Half-diminished ChordsExample: Bm7b5

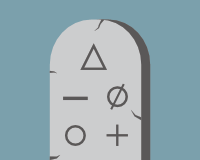

Using the knowledge you’ve learned so far, you’d call this is a ‘B minor seven flat five’ chord. And you’d be 100% correct. However, it’s more commonly known as a ‘B half-diminished chord’. It’s also commonly written using the ø-symbol, a circle with a line through it. (For more on symbols, scroll down to the section on chord symbols.)

Diminished ChordsExample: Cdim

You might’ve guessed it: if there’s a half-diminished chord, there’s also a diminished chord. They’re easily recognised either through the letters ‘dim’ or a small circle (see chord symbols section). The above example is pronounced ‘C diminished’.

Augmented ChordsExample: Caug

Lastly, there’s augmented chord. You can recognise it by the letters ‘aug’ or a small plus (see next section) right next to the root note. Pronounce it ‘C augmented’.

Alright, let’s put that to the test:

Slash Chords

Finally, you might run into are chords like these:

These are so-called ‘slash chords’, simply because the chord names use that large slash. So what does this slash mean? These chords do not mean that you have to play both chords at the same time. The ‘/note name’ tells us that we should make this note the lowest note in the chord, instead of the root note. So in the above examples, we’re dealing with a C with a G in the bass, an A minor with a C in the bass and a G seven with a B in the bass.

SECTION 3

Chord Symbols

Up until now, I’ve written all the chord names using characters that you can easily find on your keyboard. Those are most often used on the internet.

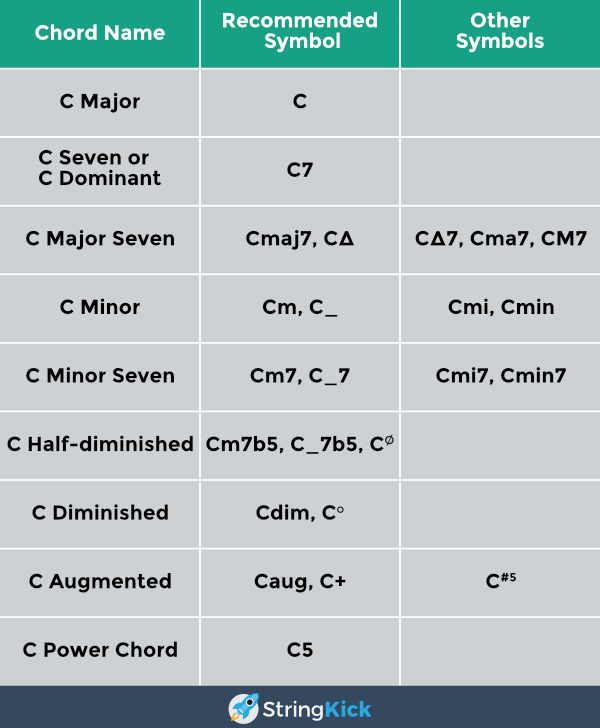

But you can also use symbols such as ∆ (major seven) and Ø (half-diminished). Though you won’t come across them a lot online (probably because they’re a pain to find on a keyboard), I love to use these symbols because they're simpler, shorter and cleaner. They're used all the time in lead sheets, mostly for jazz music. Here's an overview:

There are also some other options you might run into that I wouldn’t recommend because they’re confusing. For example, using ‘M7’ to indicate major seven is a recipe for disaster because it’s so similar to ‘m7’ (minor seven). But, you might run into these options, so it’s good to know about them.

SECTION 4

The Logic Behind Chord Names

So you know how to read chord names and you know how to play them. But what do all those letters and numbers mean? What's the logic behind chord names?

In this section, we'll take a look at the 'anatomy' of chord names: what components are they made up of and how do they fit together? Before you dive in, you should know that this section requires some knowledge of music theory:

- You know about sharps and flats

- You understand what an interval is

If you know those two things, this explanation should make sense.

If you are a StringKick All Access Member, you can of course take a course to learn all about this! Check out Music Theory From Scratch to learn all about intervals and how to play them on guitar, and how chords are constructed (and much more!).

Chord Name Anatomy

A chord is a bunch of notes sounding together. If you’d walk over to a piano right now and press a random bunch of keys at the same time, that would be a chord. Of course, most chords we use in music aren't made up of random notes, but are composed of carefully selected notes. We start with the lowest note in the chord: the root note. We then start stacking other notes on top of the root note to construct a chord with a certain mood. I like to think of these stacked notes as ingredients: by choosing them carefully, we can create chords with very specific 'flavours' or moods. We can make chords sound sad, happy, gloomy, sweet, tense, relaxed... In fact, we have set 'recipes' for chords known as 'chord types'.

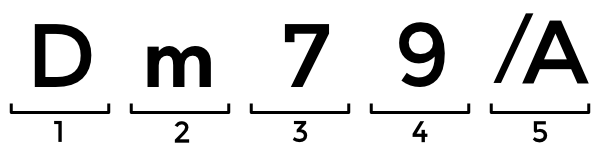

That's what a chord name really is: it's a recipe that tells us musicians which notes we should add to a chord in order to get a certain sound. This 'recipe' is made up out of five possible components, which we’ll tackle one by one. Here's the anatomy of a chord name:

- The Root

- The Chord Quality

- Sevenths or other added notes

- Extensions

- A specific bass note (‘slash chords’)

1. The Root

The first letter of the chord indicates the root note: that’s the lowest note of the chord (with the exception of slash chords, as we'll see below). So even when you see something like ‘A7b9b13’, you’ll know that the lowest note of your chord will be an A.

Think of the root note as the starting point for every chord. While everything else in a chord name gives us information about the 'chord type', the root name tells us on which note to start. The chord type is a blueprint for a building, and the root note tells us where to construct that building.

Before you move on here are some questions to test yourself and make sure you understand everything so far.

2a. Chord Quality: Major and Minor

Once we have our root note, we'll add two notes to make a chord: a third and a fifth. Now, if you're familiar with intervals, you'll probably know that we have two kinds of thirds (major and minor) and two kinds of fifths (perfect and diminished). To construct our chord, we always choose one of each: one kind of third and one kind of fifth. And which intervals we choose will determine the chord quality, the second component of a chord name.

If we choose a minor third, our chord becomes a minor chord. To indicate this, we add 'm' to chord name. But if we choose a major third, our chord becomes a major chord. However, we don't add anything to a chord name to indicate this. A chord is always major, unless indicated otherwise in the chord name.

A fifth is always perfect, unless our chord name indicates otherwise (which we'll get into in a second). So using these 'rules', you should be able to deduce what kind of thirds and fifths have been used in chords such as Amaj7, Bm7 and C#. Let's give it a shot.

2b. Chord Quality: 5 Exceptions

Nine out of ten chords will consist of a major or minor third and a perfect fifth. But, of course there are exceptions, which we'll take a look at now. If you're first getting into theory like this, feel free to skip these exceptions for now by the way!

Chords with No Third: Power chords and Sus Chords

Power chords are unusual because they consist of only two notes: a root note and a perfect fifth. They don't have a third in them: not a minor third and not a major third. For that reason, power chords aren't major or minor. They're simply a power chord. Because they only consist of a root note and a perfect fifth, we write them by adding a 5 to the note name. For example: 'D5'.

Sus chords also don't have a third in them. Sus stands for 'suspended'. The reason why we use the word 'suspended' is not worth getting into (it's related to counterpoint technique), so just read it as 'the third has been replaced by a ....' So in the case of a sus2 chord, the third has been replaced by a major second. In a sus4 chord, the third has been replaced by a perfect fourth. (Note: The fifth is always perfect in sus chords.)

Chords with a Diminished Fifth: Diminished and Half-Diminished Chords

You might've already wondered what happens when we don't add a perfect fifth but a diminished fifth. Now, the diminished fifth is quite a rough sound, which is why only commonly use it in two chords: diminished chords and half-diminished chords. These chords both consist of four notes, three of which are exactly the same in both chords:

- A root note

- A minor third

- A diminished fifth

The last note we add determines whether we're dealing with a diminished chord or a half-diminished chord. When we add a minor seventh to our chord, we get a 'half-diminished' chord. We write it as 'Bm7b5' or Bø.

To get a diminished chord, we need to add a so called 'diminished seventh'. Don't worry if you've never heard of a 'diminished seventh': it's nothing more than the theoretically correct name for a major sixth interval. (It's not worth going into why this name is theoretically correct here.) We write this chord either as Cdim or with a small circle: Co.

Chords with an augmented fifth: Augmented Chords

You’ll probably run into this chord type the least, but this guide wouldn’t be complete without it. Sometimes a fifth will be 'augmented', i.e. one fret/semi-tone higher than a perfect fifth. (In other words, the theoretically correct name for an interval that's just as large as a minor sixth interval.) An augmented chord always has a major third in it. To indicate a chord has an augmented fifth we either use 'aug' or a plus sign. So Caug or C+

Questions

Alright, let’s put all that to the test. This was a lot of information to process and remember, so don't hesitate to scroll back up to find the answers.

3. Added intervals: Sixths, Sevenths and Ninths

When we have a three-note major or minor chord, we can add an extra note to it to give the chord some extra flavour and spice. There are four intervals that are regularly added to a three-note major or minor chord: major sixths, minor sevenths, major sevenths and major ninths.

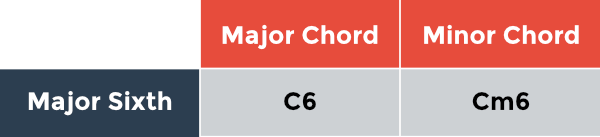

Major sixth

We often add a major sixth either to a minor or a major chord. We don't often add a minor sixth to a three-note major or minor chord (simply because it doesn't sound all that compelling). To write it, we simply add a 6 to the chord. So, here are our options:

Some quick questions:

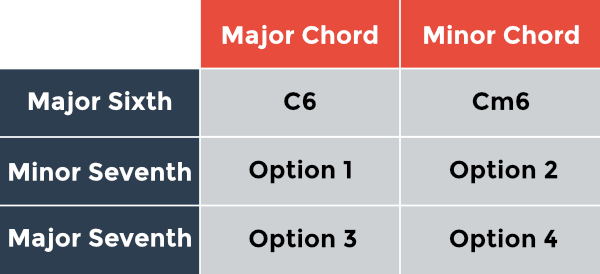

Major and Minor Sevenths

The ingredient we most often use to add some character to a chord is the seventh. To give a few examples:

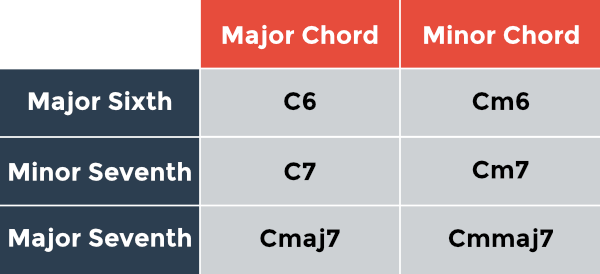

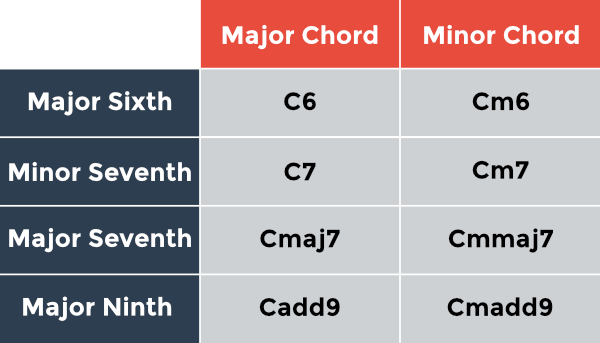

There are two kinds of sevens: the major seven and the minor seven. We can add both of those either to a major chord or to a minor chord. So that gets us four options for when it comes to seventh chords:

So how do we indicate which type of interval we've added?

- When we add ‘7’ to the chord symbol, that means a minor seventh.

- When we add ‘maj7’ to the chord symbol, that means a major seventh.

Knowing this, we can fill in our graph:

Make sense? Let’s put that that knowledge to the test:

Major Ninth

The last note that is often added to a three-note major or minor chord is the ninth. Like the sixth, there is only one (common) option: the major ninth. The only difference is that we use a slight different ‘label’ to add this ingredient to a major or minor chord: 'add9'.

Here are two examples:

Updating our chart:

And some rapid-fire test questions:

4. Chord Extensions

Adding sixths, sevenths and ninths makes our chords sound a lot richer. But - of course - we can create even more exotic sounds and chord flavours by adding more notes. These notes are what we call 'extensions'. Extensions have names like:

- b9

- 9

- 11

- #11

- b13

- 13

We usually add extensions to a four-note chord. This fourth note is always a minor seventh, unless indicated otherwise. So for example, a D9, Am9 and Cm11 all have a minor seventh in it.

As you might imagine, we can use these extensions to create dozens of different chord types. So instead of listing all the options here, it makes more sense to understand how chord construction works so you can start making your own combinations to see what they sound like. Here are just a few examples of chords with extensions:

Alright, let's put that to the test!

5. Slash Chords

Alright, then there's the very last component of a chord name. A slash with another note name.

We call these ‘slash chords’, just because of the slash it uses (nope, no relation to Slash the guitarist).

So what does this slash with another note name mean? Remember the root note, that note that constructing a chord all starts with? The root note is the first letter we see in the chord symbols above. The one left of the slash. Usually the root note is the lowest note in the chord, but slash chords are the exception to this rule: the second letter indicates a different note that should be the lowest.

Maybe you're thinking, why would we ever do this? Well, because it sounds cool. Using a different note than the root in the bass creates a different kind of sound. It's also used to make chord progressions sound slightly 'smoother' because it often allows for a bass line that moves up or down in small steps. For example, compare the first and second lines in this chord progression. The only difference is the G# in the bass in the third chord. Give it a listen.

Hear the difference? It's not that there's anything wrong with the first line, but the second line has a clearer direction. Here's another example:

The power of reading chord names and symbols

Chord names with all those letters, numbers and symbols may look intimidating at first glance. But hopefully this article has helped you to make sense of what's going on. Knowing how to read chord names and play them is an incredibly useful tool. It will allow you to play new songs instantly just by looking at a bunch of chords. It'll also make it much easier to communicate with other musician because it gives you a common language.

If you want to learn more about chord names, playing guitar chords all over the neck and music theory (and more), learn more about becoming a StringKick All Access Member! I'd love to have you on board and help you in your journey of growing as a musician!

As always, if you have questions, feel free to email me at Just (at) StringKick.com.

![Title image for Guitar Intervals: Explained Easily [Full Guide]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Guitar-Intervals-Title-Image.png)

![Title image for Learn Music Theory for Guitar [5-step Roadmap]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Music-Theory-for-Guitar-Main.png)