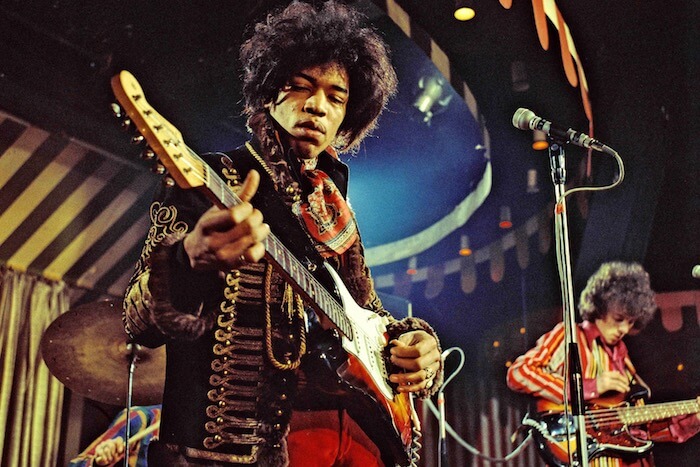

A space alien knocks on your bedroom window in the dead of night. “Earthling! We have heard word of the most sacred of objects existing on your planet. Please tell us. What is this ‘guitar’ object?”

What do you do?

- Rub your eyes and explain that the guitar is a musical instrument. It usually has six strings. You play it with two hands, where one makes the string vibrate and the other manipulates the length of each string to change the pitch produced.

- Jump out of bed, grab your guitar and play a few tunes after which you hand the guitar to the alien to give it a shot.

Learning music can feel like being a space traveller exploring strange lands. Everything is new and exciting. At the same time you don't fully understand what you're experiencing.

Invariably, other musicians will tell you to learn music theory. Advice bolstered with stories of how much it helped them and improved their playing. Then again, others will tell you to avoid theory like the plague. "Theory will inhibit your creativity and suck out all the life from your music." A list of amazing musicians that supposedly never learned music theory is drawn up to support their claims.

So should you learn music theory?

This is a question I've thought a lot about. This site is dedicated to helping anyone develop essential music skills after all. So what role does music theory play in that?

Intuitively, it makes sense to learn the ‘rules’ of music. You might look up some online resources to see what all the fuss is about, only to find that it’s dry, abstract, and kind of boring. Things just aren’t ‘clicking’. And now things have just gotten worse, because somehow space aliens are involved. I promise I’ll connect that zany story in a moment. But to know whether you should learn music theory, we first need to know what it's for.

What is Music Theory for?

Monopoly. A courtroom. A game of soccer. For some activities, you first need to know the rules. To play soccer, you need to know that you're not allowed to use your hands and you need to know how to score goals. If you don’t know the rules, you’ll have no idea what’s going on or what you’re supposed to do. Even watching a sport without knowing the rules is an alienating experience. Like those confounding English sports...

But music isn’t like monopoly or soccer. It has no ‘rules’ that should be followed at all times. You don’t need theory to sing a song or play a tune.

Music theory wasn’t created by a bunch of people that said ‘OK, this is how we’re going to do it’. Instead, people just started making music and at some point, they started to look for the logic behind it. Their question: ‘What’s going on that makes music sound good?’

That’s how music theory can help you. It provides insight into why certain music sounds good (or doesn’t). It helps you understand the sounds you already know, by giving names to them, explaining how they’re constructed, and by giving you a systematic way of thinking about music. It’s descriptive, not prescriptive.

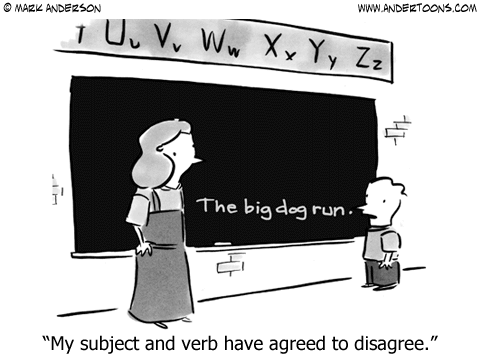

Think of it like language. Kids learn to speak fluently before we teach them grammar. No one’s teaching toddlers what verbs and nouns are. Kids learn about grammar only after their spoken language skills are already close to perfect. That means we don’t consciously apply grammar to speak correctly. We do it automatically. We study grammar to gain a greater understanding of what we’re already doing and to eliminate lingering mistakes.

In the same way, we don’t become fluent in music by learning theory. It solidifies our understanding of what we already know. What we’re already doing. It answers questions such as: Why do these chords sound so smooth together? What makes this melody sound so dark? Why does this rhythm sound so lively?

Experience versus Theory

Back to the space alien. What did you answer? You could opt for option A and explain that the guitar is a six-stringed musical instrument that produces sound by manipulating how fast those strings vibrate. But I don’t think it would convey anything meaningful about what a guitar is to our alien. It’s too vague and abstract. Though it might make a decent encyclopedia entry.

But option B allows the alien to experience what a guitar is. It conveys much more and much richer information. The alien would hear the sound of the guitar. See how your hand forms mysterious shapes and how the strings vibrate. He’d feel the metal of the strings on his tentacles (the alien in my story has tentacles) and experience the sensation of hitting the strings.

Afterwards he might ask "The rumours were true. This is a most sacred object. But how... how does it work?"

This is the time for option A. Chances are, the explanation of string length and pitch will produce a huge ‘aha!’ moment for the alien. The explanation connects a whole bunch of experiences and information that Fred (I’ve decided our alien is called Fred) has already had. This allows your explanation to rush over him like a burst of clarity.

You’ve had such experiences yourself. That moment when someone explains something you’ve been wondering about for a while and you have this huge aha-moment. Suddenly, everything falls into place and makes sense.

It’s an interesting moment, because you might think ‘Man, if I’d learned this sooner, It would have saved me SO much time and effort!’ But in fact, the burst of clarity, aha-moment would never have happened if you hadn’t first busted out a few tunes for our alien Fred. He wouldn’t have had an ‘aha’-moment, he would’ve had a ‘whatever’-moment.

The Strategy: Start with Sound

Fred’s magical guitar experience demonstrates the experience-before-theory principle. This basically means that it’s much easier to understand stuff after we’ve first gained some practical experience with it. It’s the difference between being told that a kilogram is a thousand grams, and having a weight shoved in our hands while someone says ‘This is one kilogram’. So what is the musical equivalent of having that 1KG weight pushed into your hands?

Say you’re visiting Rome for the weekend. You could spend the first full day holed up in your hotelroom studying the map until you can reproduce it with pinpoint accuracy and lightning speed. But wouldn’t you be better off exploring the city, wandering through the streets, and asking for directions every now and then? When you look at a map at the end of the day, things will all come together. You’d know what the streets look like. Where that one pretty building was. And you could figure out which parts of the city you’ve seen and which you haven’t. The map would make sense.

Music theory is like a map. It’s not that interesting if you’ve never visited the city before. That’s why it’s better to learn to play a bunch of music first, before you try to understand that music. Start with sound. If we don’t experience the music first, theory won’t make as much sense. Music invokes all kinds of emotions and feelings in you. Those sensations are like little hooks that you can connect theory to. Without those hooks, theory wouldn’t make sense and wouldn’t stick. The hooks bring the theory to life.

So, should you Learn Music Theory?

Music theory gives us a deeper understanding of the music we already know. But you don’t need theory to play music, just like kids don’t need to be aware of grammar to speak their native language.

But if you’re looking to understand a bit more about what you’re doing, the question changes. It’s no longer if you should learn theory, but when you should learn it. The answer: explore the city before you study the map. Start with sound. As long as you’re starting with sound, you’ll be learning theory that makes sense to you and avoiding the stuff you don’t need.

It can be hard though to resist the temptations of fellow players convincing you to learn topic X, Y, or Z because it will ‘revolutionise your playing.’ Keep in mind that they might be overestimating the importance of the topic because of their own burst-of-clarity-aha-moment when they learned that bit of theory themselves. Ask them to explain exactly how it will improve your playing. It’ll help you find out if it’s relevant for you and your musical goals and ambitions. ‘Trust me!’ isn’t a good answer.

If you don’t really know why you’re learning music theory, don’t. Always be aware of the question you’re trying to answer. Why do these chords sound good together? Why do these notes sound good over this chord?

So if you want to get started with music theory and gain a deeper understanding of why music moves you, here’s the next step. Pick a (part of) a song that you love and start investigating why you like it. Try to pinpoint what it is that you love so much, whether it’s a melody, a bunch of chords or a drum groove. If you need some inspiration, feel free to grab my PDF checklist with sixteen questions to get you started:

If you're interested in a hands-on, 'start with sound' approach to learning music theory, check out Music Theory From Scratch. This course, made specifically for guitar players, takes a super practical approach to learning theory. As you've probably guessed, yes, there's lot of great music in the course! You'll see everything you learn in action in awesome song examples (that you can play along with if you want to). The course is fully included in the StringKick All Access Membership, so if you're interested in getting a better handle on theory, and deepening your understanding of music, check it out! I'd love for you to join the site and help you on your musical journey.

Finally, don’t hesitate to email me if you want some help: just(at)stringkick.com!

![Title image for Learn Music Theory for Guitar [5-step Roadmap]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Music-Theory-for-Guitar-Main.png)

![Title image for How to Read Chord Names and Symbols [Complete Guide]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Read-Chord-Names-Symbols-Title-Image.png)